0

In my first trip to Java, I wanted to become a dalang. My most recent trips have been defined by the pursuit of a PhD degree. There are some similarities in my two desires to become something else, or rather something more. In the felicitous accomplishment of either of these endeavors, I would undergo a change in status and gain social recognition. In both cases, my name would grow: two letters would be prepended to it. If a certain community of people would recognize my work (i.e. my performances), I would become ki Miguel, if another community would validate my work (i.e. my dissertation), I would become Dr. Escobar. Although I have shifted my focus and objectives, my daily activities in Java have not changed much over the past six years.

In other words, although the objectives and outcome are different, in pursuing my desires to become something more, I have carried out the same set of activities for the past six years: taking pictures, buying puppets, taking lessons, talking to people, drinking industrial amounts of sweet tea, recording performances, translating texts and writing down notes on my laptop. In one case, I was performing and learning to perform, while in the other, I was building an archive and writing a dissertation. So, this leads me to pose the following, seemingly inconsequential question: is performing different from archiving?

Although many people would protest at the question and would say it depends!, I would like to consider two interesting answers to this question. The short answer is yes. The long answer is no. I will use these possible answers as a starting point for reflecting on the methodological implications of researching a performance tradition. But first, let's consider what the word archiving means.

According to Derrida, the word comes from the Greek word aekheion, which referred to the residence of the superior magistrates or archons. This was a place where the official documents were filed and the archons possessed the archives and the right to interpret them (Derrida 1996: 91). Diana Taylor suggests a different etymology, stating it comes from the Greek word arkhe, which “means a beginning, the first place, the government” (Taylor 2003: 19). This leads her to conclude that “the archival, from the beginning, sustains power” (Taylor 2003: 19), which is not dissimilar to Derrida's contention. The possible meanings of this word 3000 years before the invention of YouTube should not necessarily matter to us today. Words are notoriously plastic in their meanings and their Greek origins are not always illuminating. However, sometimes the origins of words do provide interesting historical background.

The idea of the archive as an expression of power seemed to be integral to thinking about archives for a long time. A similar argument seems to be present in the reflections of Foucault, who describes the archive as “the general system of the formation and transformation of statements” (Foucault 1972: 130). However, his notion of the archive encompasses many different practices. As Mike Featherstone points out, the Foucauldian notion of the archive “has a virtual existence and amounts to the system which governs the emergence of enunciations” (Featherstone 2000: 169).

It is worth interrogating the validity of these claims in a time when people in many parts of the world are constantly engaging in self-archiving projects. This has been facilitated by the availability of cameras, smartphones and web platforms such as YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. In our times, the distinction between those with power to archive and those without it requires a nuanced understanding. Of course, we could still identify the mechanisms of power at work, arguing that YouTube is owned by the biggest company in the history of the planet or by pointing to the gross inequalities of the “digital divide” that allow some people to archive themselves 24/7, whereas others have to walk several kilometers to the nearest computer. True as this may be, there is a more complicated distribution of power than the ones implied by the theorists quoted above. In this writing, I aim to show that the availability of technology and the naturalization of everyday archiving practices complicate the relationship between archiving and performance. As Derrida himself would concede: “that which is archived differently is lived differently” (Derrida 1996: 18). But let us start with an exploration of how an archive differs from a performance.

A succinct distinction between archives and performances can be found in Diana Taylor's classical distinction of the archive and the repertoire. “Insofar as it constitutes materials that seem to endure, the archive exceeds the live” (Taylor 2003: 19). In contrast, the repertoire “enacts embodied memory: performances, gestures, orality, movement, dance, singing – in short, all those acts usually thought of as ephemeral, nonreproducible knowledge” (Taylor 2003: 20). Although this opposition seems absolute at first glance, she does allow for two complicating factors.

The first one is that power permeates both: there are state-sanctioned repertoires and official archives that are expressions of power. Likewise, there are subversive repertoires and unofficial archives that aim at destabilizing or at least offering alternatives to the ones sanctioned by official power. The other complicating factor is that differences between the two are not always absolute, and they are connected to one another in a dynamic relationship. Despite considering this complexity, Taylor still maintains a division:

The live performance can never be captured or transmitted through the archive. A video of a performance is not a performance, though it often comes to replace the performance as a thing in itself (the video is part of the archive; what it represents is part of the repertoire) (Taylor 2003: 20).

Performance's only life is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented, or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does so, it becomes something other than performance (Phelan 1993: 146).

In a controversy that has been well documented and which is often revisited, this argument was notably contested by Phillip Auslander who aimed to “destabilize these theoretical oppositions of the live and the mediatized” (Auslander 1999: 48). He suggests that “it is not at all clear that live performance has a distinctive ontology” (Auslander 1999: 57).

Mediatized forms like film and video can be shown to have the same ontological characteristic as live performance, and live performance can be used in ways indistinguishable from the uses generally associated with mediatized forms. Therefore, ontological analysis does not provide a basis for privileging live performance as an oppositional discourse (Auslander 1999: 184)

In her 2010 book on Cyborg Performance, Jennifer Parker-Starbuck historicizes this controversy and labels it a “dated” disagreement, suggesting that history has sided with Auslander and confessing to a “tacit acceptance of Auslander's argument” that the live is already mediatized “in the contemporary moment of globalized technology” (Parker-Starbuk 2010: 9). Although she is admittedly seduced by Phelan's concepts, she ascribes to them little more than a nostalgic and historical interest, when she identifies her own “desires to use the term ‘live' as Peggy Phelan does, to mean a bodily presence” (Parker-Starbuk 2010: 9). Contrary to Parker-Starbuck's approach, I would suggest that Phelan's critique can be used to do more than just recuperate the notion of bodily presence. Despite the fact that the debate has been documented extensively (Dixon 2007, Giesekam 2007 and Reinelt and Roach 2007), the important questions raised by Phelan have not been settled once and for all and any archiving practice needs to take her provocations seriously. If we are to build an archive of performance recordings we need to ask ourselves: what will be lost and what will be misrepresented in the archive?

In order to answer this, let us consider the specific kind of archive that I am talking about. As I mentioned in the introduction, a substantial part of my PhD fieldwork involved traveling around Java to find existing recordings of wayang kontemporer performances. In some cases, I was given the raw video materials and I had to edit them myself. For five of the performances, I was in charge of the recording and the editing from the very beginning. I then added English subtitles to all twenty-four performances and designed a website in order to display the videos, subtitles and my translation notes. Against the backdrop of Peggy Phelan's arguments, what are we to make of these edited, digitized and subtitled traces of a live performance? Moving away from the terrain of purely ideological critique, we might take a moment to consider the practical considerations of putting an archive together, which can help us further identify the differences between a live performance and a recording. The following remarks are inspired by my own archival practice.

There are at least four specific differences worth discussing between watching a performance live and the watching it on video. First, video fails to take into account the “atmosphere” of the performance. As Catherine Diamond notes:

Only by watching performances in situ, among the spectators for whom they are intended, do we get a feel for the theatre's cultural import as a creative response to the social changes being experienced by both spectators and performers (Diamond 2012: 22).

Jan Mrázek says something similar in his examination of the differences between watching wayang live or on television (or on a computer screen for that matter). In the latter case(s) we are not physically present at the place of the performance and this means we only experience audio-visually what is in reality a multi-sensorial event. The haptic and olfactory qualities of the performance, such as the temperature and scents (or smells) of the venue, the food we eat and the drinks we consume, are absent from these recordings. The same is true for the conversations that are part of watching wayang in situ, which do not get transferred to the televised experience. According to Mrázek and his Javanese informants, these aspects are not superfluous elements, but integral precursors to the joy of watching wayang live:

Part of the pleasure of watching wayang directly, it is emphasized, is talking to people, meeting new friends, and eating or drinking together in the stalls that surround the performance area, and this experience is lost, or altered, when wayang is seen on television (Mrázek 2002: 340)

Another difference between live and mediatized performances is that performances can be changed for the sake of the recording, when they are staged specifically for the cameras. Felicia Hughes-Freeland talks about an arja performance in Bali that was recorded for State Television. She interviews two people who describe how the live and the recorded performances differed from one another: the technical precision was higher in the recorded one, but this one did not allow for improvisation and interaction with the spectators. The live performance was also “livelier” (Hughes-Freeland 2009: 56). To her surprise, however, her informants considered the mediatized performance as having more taksuh, a term she translates as “the power of the performance endorsed by supernatural forces” (Hughes-Freeland 2009: 56). The mediatized version had greater ritual potency and was superior to the other in some technical aspects. Sometimes, as these commentaries suggest, recordings are not necessarily worse or less complete. As I will explore later, recordings can sometimes be considered better than the live performances.

Another thing to take into account is the fact that a video represents what is just a snapshot of an ongoing process of constant change. Sarah Jones, Daisy Abbott and Seamus Ross explain that:

Archives tend to focus on a single end product, yet performances are constantly in a state of becoming and have no definable end. The archive consequently enforces a false sense of completeness on a performance event that is part of a much wider work. It is impractical to separate individual instantiations of a performance from the process of their creation and unrepresentative to force them to fit this model of archives (Jones et al 2009: 160).

In other words, open-ended and ongoing processes become fixed. However, it can be argued that most spectators only watch an instance of a performance and do not witness the entire process of transformation in which that particular event partakes.

Hughes-Freeland identifies a point similar to that of Jones et al when she suggests these performances, by virtue of being recorded, acquire an “exemplary nature” (Hughes-Freeland 2009: 57). Subsequent viewers of the recording could be misled to believe the recording represents the most common characteristics of the specific show, since “it will be seen repeatedly.” This is perhaps more applicable to traditional performances than to contemporary ones. People will not necessarily think that a wayang kontemporer recording has exemplary value for the whole of wayang, but they might believe that is what a particular dalang's work is always like. In the early days of Wayang Hip Hop, I remember inviting a friend to watch one of their performances. She had only seen poorly made YouTube clips and was reluctant to join me. However, when I showed her a better recording, which was not available online at the time, her attitude changed and she decided to join me in the end. This just stresses the same point; namely, that recorded performances give a limited view of long and dynamic processes.

Watching through a screen also differs from the embodied way of looking at a live performance. Jan Mrázek addresses this by describing the way in which both his informants and Maurice Merlau-Ponty talk about perception. Perception, according to the French philosopher, cannot be cut apart from movement and from our bodies. Perception is situated and embodied. Of course, when we watch a performance on a computer or television screen, we are not having a “disembodied” experience. Not being physically present at the performance just means we are physically present somewhere else – that other place will still be a venue full of multi-sensorial stimuli, and even if we do not use our bodies to move around, we will still interact with a computer mouse, touchscreen or remote control. However, the way in which we look at the performance is different because “perception is no longer what Merleau-Ponty claims it to be [...] [b]etween my body and the world there is television” (Mrázek 2002: 338). That which is to be looked at has been pre-selected by the cameraman and the editors.

The problem is that television represents my eyes, but it sees differently than me; it “edits” differently than I “edit” what I see. One reason why television, compared to myself, is a bad “editor” is because it is not me: I choose myself what I look at, on the basis of what I see, while television chooses that for me, as my deputy, and its choices are not always the choices I would make, and, more importantly, the whole process of seeing is different, as is my involvement in the process (Mrázek 2002: 350).

As Mrázek shows, sometimes editing is done in a way which is different from our personal preferences. Some of his interlocutors, notably angered by this situation, described the editors and cameramen as “tyrants” or “idiots” who didn't understand wayang. Sometimes his interlocutors said that watching wayang on television was like following a jumping squirrel (bajing loncat), since the close ups carelessly pieced together resemble the travels of this jumpy creature from branch to branch. He concedes that watching wayang is not exactly like this, but that this metaphor does provide insight into the differences between experiencing a performance live and through television.

Besides the obvious downside, his interlocutors also identify a variety of advantages to watching wayang on a screen. On the upside, it affords the spectators the convenience of not having to travel to the performance and of being physically present somewhere else. Although this is not applicable to television, we could add to the list the fact that, in the case of the archive, recorded videos allow us to study wayang better, since we can rewind and replay different fragments.

If we are aware of all these differences and treat them with creativity, awareness and humbleness, making and archiving videos of performances has extraordinary possibilities for the academic discourse on the performing arts. They can enable us to convey more complete renderings of the performances that we would be able to achieve through writing alone. This is already impacting the ways in which knowledge about the performing arts is being produced. However, a more profound revolution of the ways in which performance studies research is conceived and practised is perhaps in store.

This does not mean that writing will be displaced. Writing (and other modes of description) can help to partially direct the attention of the viewers to the things that are lost in the recordings, which were considered above: the fact that they are snapshots of longer processes, the impact of editing, and the differences in multi-sensorial perception they entail. Writing also highlights the discursive aspect of performance, putting the performance into interaction with discourses not necessarily part of the performance. This dissertation combines texts, diagrams and audiovisual excerpts. In the texts, I try to account for all the things that the videos alone cannot. For this reason, I place a heavy emphasis on anecdotal narratives in my introductions to each of the sections of Chapter 2. Through writing, we can point to, if not fully recuperate, those elements of the experience that might be lost and humbly accept that our editing and selection process might not be the best one – in the minds of the users of the archive. We can be reminded of the words of Jones et al:

The temporal nature of performance causes tension: the fear of loss leads to an urgent desire to counter this through documenting, while the loss inherent in this process leaves many dissatisfied with the outcome (Jones et al 2009: 167).

This, of course, applies to video as much as it applies to writing or other modes of documentation. However, I will insist that video offers important advantages to just writing about performance in general and about wayang specifically. Henrik Kleinsmiede's review of the Dutch scholarship on wayang diagnoses it with a severe case of “mentalism,” that is, an emphasis on reason and language. He then links this to contemporary scholarship, which also shares with previous colonial commentary four characteristics he lists disapprovingly:

(1) a continuing dominance of mentalism (to the detriment of the body), (2) a belief that only the linguistic and symbolic can articulate [the performance's] meaning, (3) the development of a very specific genre of writing (academic literacy), and (4) a subsequent (over)reliance on printed media (Kleinsmiede 2002: 65).

His prescription against these evils of academic writing is a dose of affective writing which he describes as “novelistic,” as opposed to the heavily nominalized and impersonal voices that dominate wayang discourse.

By novelistic I mean writing intended to impact upon the body as well as the mind (that speaks to emotions as well as to the intellect) and in which the personal voice/perspective is not lost but actively celebrated (Kleinsmiede 2002: 61).

I agree both with his invitation to write in a more affective mode and with his remark that probably the only book in the entire academic corpus on wayang to have achieved this is Jan Mrázek's Phenomenology of a Puppet Theatre (Kleinsmiede 2002: 60). Kleinsmiede also identifies another strategy to move away from mentalism: relying on audiovisual media to recreate “a multitextured semiotic that includes sound, vision, taste, and even the olfactory” (Kleinsmiede 2002: 60). The material in this interactive dissertation stops at the second sense he mentions, but I agree with his hopeful remark that:

Perhaps this essay shouldn't even be here... it might be better placed elsewhere, in another mode, and possibly one not yet invented. In the interim, it might be better placed on the internet (Kleinsmiede 2002: 39).

This dissertation tries to take on Kleinsmiede's suggestion and provide for the kind of affective and sensorial experiences that writing alone might fail to do. The reader will be the judge of the extent to which this goal is achieved.

Thus far, I have illustrated the key problems and advantages of using video. I will contend, however, that the advantages greatly outnumber the pitfalls, especially when used wisely and humbly; that is, when explanations accompany the visual material, directing attention to things not captured by the recordings. However, even if we are able to account for all the problems and advantages of using video from a technical perspective, there is another set of issues that we need to be careful about and these relate to the ethics of representation.

Those engaged in researching other cultures have to deal with these questions, one way or another. How is it possible to represent the others, without committing the easy mistakes of either excessive reductionism or ‘otherizing practices' and without the cultural insensitivity of glossing over important differences? How can we be respectful and yet acknowledge that we want to say something about ‘other' modes of making sense of the world and that we find these interesting, partially, because of their difference?

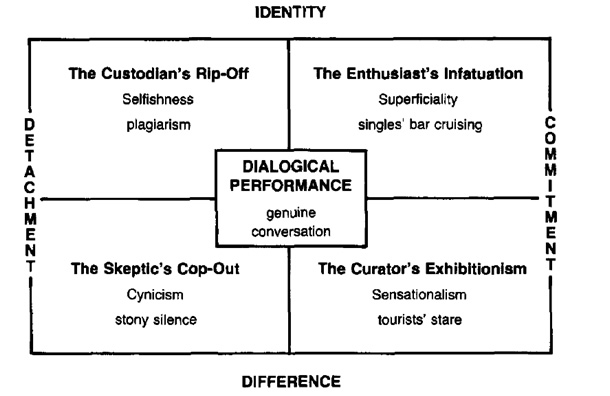

Dwight Conquergood identified four capital sins into which we can easily fall when we are studying and representing those from whom we have an “aesthetic distance.” These sins are the custodian's rip-off, the enthusiast's infatuation, the skeptic's cop-out and the curator's exhibitionism (Conquergood 1985: 1). He suggests a diagram where these are plotted against two axes: identity versus difference and detachment versus commitment. In the center, lies the happy dream of a dialogical performance: a true conversation (Figure 1.3).

I must confess I have incurred all four at different stages of my research (and perhaps continue to do so). But the curator is the one that applies the most to the problems inherent in archiving: isolating and codifying the experiences of others and presenting them to people who are in faraway places. The results of this attitude:

[R]esemble curio postcards, souvenirs, trophies brought back from the tour for display cases. Instead of bringing us into genuine contact (and risk) with the lives of strangers, performances in this mode bring back museum exhibits, mute and staring (Conquergood 1985: 7).

There are many important ways in which it is different to write a digital dissertation about wayang than it is to talk about the Hmong refugees in the US (which is what Conquergood had in mind at the time of his writing): one such difference is that the creators of the kontemporer performances fully understand the ways in which their work will be represented; the other is that they are extremely familiar with archiving practices. Even in cases where the dalang have not recorded their own work directly, their performances are often seen by at least one camera eye: cameras and smartphones are ubiquitous in Indonesia (the country with the highest number of BlackBerry users in the world) and people often upload those pictures to YouTube and Facebook (Indonesia also boasts the third largest population on Facebook). In many ways, cities in Java are a lot more mediatized than certain places in Europe. Internet access is ubiquitous and it is not impolite to look at your smartphone when you are having a conversation. Therefore, it is also sensible not to exagerate the application of Conquergood's claims to this case, where there is no excessive 'aesthetic distance' between the researcher and the artists.

At least consciously, I believe none of my words could be interpreted in a way that would deny the dalang “membership in the same moral community as ourselves” (Conquergood 2007: 7), which is the basic flaw of exhibitionist curators. And yet, as I mentioned earlier, I am constantly expressing and celebrating their difference. Granting others both difference and equality is a fine line to tread, and it can only be achieved through the dialogical performance that Conquergood suggests. These are not merely theoretical concerns since they are reflected in the specific framing and presentation practices carried out by scholars and archivists. We should certainly be accountable for our presentation and research practices. In which ways, then, can I guarantee that the dissertation is consistent with dialogic performance?

I have tried to address this by returning continuously to Java after my initial fieldwork, discussing my approach, and showing this website to the dalang. I have also organized discussions with Indonesian academics and artists at the Indonesian Visual Arts Archive (IVAA), which is a partner institution for the hosting of the Contemporary Wayang Archive. Conquergood suggests that doing research and presenting its findings are never passive activities. The performative turn in anthropology (to which Conquergood's writing contributed) stresses that research and research-presentation are necessarily performative. In a similar vein, we should recognize that archiving is also performative in a similar sense: it is never passive, nor transparent. Jones et al sum this up in the following way:

Arguably, all archiving is performance: records are surrogates that provide a window onto past moments that can never be recreated, and users interact with these records in a performance to reinterpret this past (Jones et al 2009: 166).

We have thus reached the long answer, performing is not completely different from archiving. Collecting and organizing records are also performative activities in the way some anthropologists and other social scientists have suggested; that is, the creation of knowledge is constructed and brought into existence through interactions between research participants and researchers. This constructed, active aspect of knowledge formation is highlighted in the engagement with a digital archive. Users are never passively consuming the archive; by reading subtitles and videos, fast forwarding and rewinding and re-watching the fragments, they are also constructing their own meaning. Jones et al go as far as to suggest that a digital archive is a set of codes that exists only virtually and is only ‘performatively' brought into visibility every time the code is executed: “digital records are inherently performative, only coming into existence when the correct code executes the data to render a meaningful output (Jones et al 2009: 170).”

To be performative, in this interpretation, means recognizing the constructedness of knowledge generation and presentation. Though this claim is haunted by a sense of limitation, in its acceptance, we can also find a path towards creative inclusivity and dialogue. In other words, we can and must continuously find new ways of incorporating other points of view that pay due justice to the specificity of that which is being presented. The archive should be in a state of constant change and self-reflexivity, as Jones et al suggest: “To maintain its significance, the archive, like a language, must be open to change and remain in active use” (Jones et al 2009: 169).

I agree fully with this last remark and this website has benefited from the active use by different people who have provided me with feedback, both in relation to its appearance and its conceptual underpinnings. However, the questions I examine in this section are not fully settled, once and for all. I don't think that a performance archive can ever fully resolve the tension with its others (the live performance and the cultural context from where the material comes from). At best, those tensions can be highlighted and critically explored, which is what I do, both here and throughout the dissertation. In the next section, I describe the specific practices of archiving that I carried out and the ways in which they helped me refine my methodological approach.

CLOSE [X]