0

The late Slamet Gundono was the most famous and the fattest dalang in Java. Both superlatives are empirically verifiable. If you ask around, both among foreign researchers and local wayang kontemporer aficionados, they will certainly agree with the fact that he was, if not the best, at least the most famous. He was “perhaps Java's best known post-traditional puppeteer” (Cohen 2014: 4) and “his experimental art earned him travel to faraway countries like Britain, Germany, The Netherlands and Japan for performances” (Panji 2000).

If you ever saw him – live or through videos – you will agree that his prominent physical presence was hard to miss, especially since he referred to it often. In almost every performance, he mentioned jokingly his enormous weight. "In Java lives the fattest dalang who has ever lived, called Slamet Gundono," he said, speaking of himself in the third person in the opening lines of a wayang show that was recorded for a German television broadcast, “but he is also the most handsome” (Pertaruhan Drupadi, 2006). These bits of self-deprecating and self-aggrandizing humor elicited roaring laughter from the musicians, and the dalang continued with the show.

In certain parts of the world, it would be very rude to call someone fat, especially an artist one admires and whose work one is going to talk about. However calling oneself or others fat in Java seems perfectly acceptable. I have witnessed the shock of many foreigners when they themselves or other people are called fat directly. Likewise, I have seen many Javanese people shocked when foreigners say things that would not necessarily be offensive in other places (for instance, when they show visible signs of anger and yell at others).

Trivial as these reflections may appear, these differences matter. They are relevant to wayang and to the academic discourse on wayang. This is a piece of writing about wayang performances but it is also about the ways people talk about these performances in Java. And the way people talk about performances is never too different from the way people talk about people. Discussions about art and the most mundane assertions found in everyday conversation are part of the same discursive sphere. The aesthetic, the philosophical and the worldly realms are intertwined in the way wayang is created, enjoyed and talked about. Wayang is interesting to me because it can potentially address every aspect of life in Java. If we accept this proposition, we must also concede that many observations about everyday life in Java are relevant to wayang scholarship. By stating this, I don't aim to suggest that the ontology of wayang can be encapsulated or reduced to a collection of notes about curious cultural differences, I merely wish to suggest that the flimsiest assertions about culturally-contingent language usage are not fully out of the scope of an academic inquiry into wayang. In this dissertation I aim to develop a digital platform to compare a wide range of wayang performances and to interpret what they say about contemporary Java. In order to accomplish these objectives, I try to develop a culturally sensitive approach and recognize that talking about wayang implies talking about the way people talk about other things as well. A central tenet of this dissertation is that wayang kontemporer is a way of "making sense"" of and speaking about the contemporary world. I do not mean to say that all the Javanese people talk about it in the same way, but I will recognize my intellectual debt to the specific ways some people have talked with me about it. My thoughts and experiences of wayang have been deeply influenced by conversations with friends, teachers and artists, one of whom was Ki Slamet himself.

Born in Tegal in June 9 1966, Slamet Gundono came from a family of traditional puppeteers but he also received dalang training at the Indonesian School of the Arts in Surakarta (ISI-Solo). In the late 1990s he achieved national fame with his wayang suket. Suket means grass in Javanese and in wayang suket shows he used puppets made from grass. This was not his invention; wayang made of grass has probably existed for a long time. Nonetheless, as a commentator writing in The Jakarta Post said, “Slamet is the one who has elevated the straw puppet status to a performing art” (Ganug 2000) and he has brought a new sensitivity to the usage of grass:

Wayang suket allows full freedom for the audience to build on their unlimited imagination. The philosophy of grass as an ever-growing plant needing only water and sunlight represents the spirit of an art that generates pride and strength of imagination (Ganug 2010).

Although Slamet Gundono used stories from the Mahabharata, he did not rely on the wayang performance conventions. He often spoke directly to the audience, alternating between singing and narration, using the puppets only now and then. He was also a famous singer, and his songs did not completely follow wayang conventions. In his performances, he incorporated new music by singing and playing the ukulele. His storytelling technique was not traditional either; he impersonated characters and looked spectators in the eye when speaking, generating a unique sense of theatrical intimacy. His puppets were not limited to suket creations; sometimes he would use sticks, cell phones and other common objects:

Unlike most dalang, clad in a traditional suit with a headcloth and a kris, Gundono sometimes appears without a shirt, or dressed like a cowboy. His other performance media, apart from the main characters and gunungan (mountains symbolizing human and spiritual worlds), are made from vegetables such as chili, cucumbers, tomatoes and onions stuck to a banana tree stem (Ganug 2010).

To this day, his suket shows remain his best known works. But he also engaged in a variety of projects, collaborating with other artists from both Java and abroad. In Wayang Tanah, his production team dug up a 25 square meter cavity in the ground in which he performed a wayang show where the "puppets" were made of mud. The performance combined storytelling with a ritual to celebrate the beginning of the rainy season. Cebolang Minggat was a collaboration with the French writer Elizabeth Inandiak that explored the sexual and spiritual adventures of Cebolang, a character of the 18th century Javanese literary work Serat Centhini whose controversial content has occluded this work from public consciousness, although some people consider it the greatest Javanese work of literature. Besides being a creative dalang and a famous singer, he was also a good and patient teacher. Some of the most pleasant memories I have of my "fieldwork" are the long conversations I had with him in his house near Surakarta. On one such occasion, in April 20 2012, I asked him if he liked the term wayang kontemporer, which is often used to describe his work. I wanted to know if he felt it was an accurate term to describe what he does with wayang. He just smiled enigmatically and said nothing. I thought I might have asked something silly or annoying and did not say anything either, I just kept drinking my tea in the hot afternoon. We were sitting in a pendopo in front of his house, the place where he usually rehearsed, while his assistant was examining a pile of external hard drives trying to find a performance video I was interested in watching. "Wayang kontemporer is alright," he said after several minutes, "but you could also talk about it in other ways. Maybe flood wayang is better [wayang banjir]."

In the past there were seasons. Life was organized according to them and so was wayang. You would make a performance for a wedding and for the start of the rainy season. But now nature is not predictable anymore. We have long dry periods and these awful floods. So now we have to create a wayang that suits these crazy times. A wayang for a world where there is no natural order and no social order anymore. If the times are crazy, the dalang must do the same! [nek jamane edan, dalange kudu melu edian ha!]

This dissertation is about the crazy wayang performances of the crazy dalang for these crazy times. Since the term wayang banjir has not yet caught on, I will keep referring to them as wayang kontemporer and I will define these performances as those re-elaborations of wayang which are a combination of wayang and something else, but where the dalang and at least some of the conventions of Javanese wayang kulit are still central.

Most of the performances I will refer to are among the 24 wayang kontemporer performances which, in a recorded version, form the current collection of the Contemporary Wayang Archive (CWA). Collecting, recording and subtitling the videos were essential activities during my PhD research. In Positionality: Researching Wayang as a Digital Archivist, I talk more about the methodological implications, the joy and the headaches of this process. I also argue the importance of using digital tools for the recording, analysis and presentation of my research, framing this dissertation as a digital humanities project (See Approach: An Essayistic Ontology). At this point, I will just define the kinds of shows which were considered for the archive and for this writing. The scope of this research was limited to wayang shows with the following three characteristics: the dalang is the central figure, Javanese wayang kulit conventions are used, the shows were created in the post-Reformasi era.

Wayang kulit has sometimes been translated and talked about as a form of “shadow theatre”, and seen in comparison with other shadow theatre forms from elsewhere in the world such as the Taiwanese ping or the Turkish karagöz. Personally, I find the term shadow theatre misleading and I would suggest that wayang kulit is largely the art of the dalang. Few people watch the shows from the side of the shadows (see Space) and the dalang is a central element of the shows. He (rarely she) is a philosopher, a comedian, an orchestra director, and a storyteller. Part of the joy of watching wayang is seeing how the dalang brings the story to life, animates the puppets and interacts with audience members and musicians. Kathy Foley suggests that the notion of a controller is very important to certain traditional theatres and links this to the way rituals are organized. In rituals, as in traditional theatres, there are always two figures: "the dancer and the danced," or the controller and the medium, which, she suggests, is similar to what happens in trance dances: "Clearly the two-role division of the trance form (medium and spirit controller) has its parallel in the dancer-dalang dichotomy in theatre" (Foley 1985: 42). Although she formulated this role duality within the Sundanese context, it applies to Javanese performances as well. This criterion of the centrality of the dalang figure in the contemporary wayang performances covered in this dissertation leaves out performances such as those by Teater Koma which are inspired by wayang stories but where there is no art of the dalang, such as Semar Gugat (1995). However, it does include Teater Koma's Sie Jin Kwie and Sie Jin Kwie Kena Fitnah, where a dalang is one of the performers.

In the shows considered in this dissertation, Javanese wayang kulit conventions are used, even if they are completely reinterpreted. Therefore, this excludes contemporary shows that only use wayang wong or wayang golek conventions, like the shows by Asep Sunandar Sunarya, described by Andrew Weintraub (2010). The selection does include shows that integrate wayang wong and wayang golek elements within wayang kulit, such as Aneng Kiswantoro's Sumpah Pralaya and Mirwan Suwarso's Jabang Tetuka. However, the contemporary work of Ria Papermoon and her company falls outside of the scope of the present dissertation.Traditional wayang kulit as a form has a distinct integrity as a medium, a set of stories, aesthetics and spectatorship conventions. These have all been very well documented and therefore this project has chosen to focus on the reinterpretations of the form which can still be thought of as wayang performances. This is the reason why the centrality of the dalang figure has been considered a key criterion.

Although wayang kontemporer shows have a long history (which will be considered when pertinent), the scope of this research is limited to works created after 1998, when Suharto's New Order came to and end. After this date, incipient democratization, increased digitization and accelerated globalization have allowed the creation of a great variety of shows about which there is very little scholarship.

With these criteria in mind, I selected 24 performances, and traveled around Java making and collecting recordings, watching performances and talking to people. I saw most of the performances live, and many of them on several occasions. In some cases, I was personally responsible for recording and editing the videos. Upon returning from Java, I have seen those videos repeatedly with different purposes in mind. First, to add English subtitles to them. Second, to complement my analysis of them. Third, as supporting materials for the classes I teach. I began my analysis of the performances when watching them live. Watching them on video prompted memories of those experiences but also opened up new analytical possibilities: by allowing me to concentrate on things that I missed on the first watching and by facilitating a comparative approach with other performances.

Consequently, I have seen them on video many more times than I saw them live, and this has necessarily affected my perspective on them. The multiple viewings have allowed a comparative analysis of their salient features but they have also flattened the performances to the same format, abstracting them from their original context. In this dissertation, I address this bias by providing explanations of the contextual conditions of performance where pertinent, which are taken from my fieldwork diaries. However, one of the reasons this dissertation is presented in an online form is so that it can include video excerpts within the text. In order to complement their reading experience, the users of this website can also view radar diagrams that display the main characteristics of the performances being analyzed.

The analysis in this dissertation cuts across the different performances and one disadvantage of this is that the individual performances fade to the background. This analysis might also be confusing to follow for people not familiar with these 24 performances. Therefore, the diagrams present a reading aid, displaying the main characteristics of each performance and allowing for an alternative way to navigate through the chapters that make up this dissertation. The chapters of this dissertation form part of a sequence. However, each of the chapters can also be read on its own by clicking on the diagrams (left-hand panel) rather than on the table of contents (the right-hand panel).

Although the analysis uses videos and interactive displays, I must emphasize that this is a study of performances and it does not analyze films, interactive video-games and novels that also deal with re-elaborations of wayang. I am also aware that there are similar forms among Java's neighbors, such as Kelantan in Malaysia, and Bali. In Singapore, the term wayang has also been used to refer to Chinese street opera performances – a fact which, according to Paul Rae, attests to the “intercultural mobility of the idea of wayang” (Rae 2011: 74, original emphasis). I agree with his contention that following this idea could be used to "trace the associative network in which such performances are embedded" (75), an analysis that would take us far beyond the borders of Java.

However, I have chosen to take a different route and concentrate on the specific ways in which wayang functions within Java. There, it is the most respected form and its constant use by numerous institutional actors gives it an official status that it does not have elsewhere. What I mean by official is that wayang iconography and stories are used by prestigious government institutions and sponsored during official events. If we were to look at this official visibility and respect only, wayang kulit in Java is perhaps more similar to khon dance in Thailand than to wayang kulit in Bali. Although it is also very alive there, wayang is hardly the most respected tradition in Bali, a position that is perhaps occupied by dance. Another difference is its function. According to I Nyoman Sedana, even the most innovative forms of wayang in Bali have a decidedly ritual function, which is not true for wayang kontemporer shows in Java, which usually do not have a ritual function. Note the way in which he talks about a show by I Made Sidia that was aimed at restoring the natural balance after the 2002 Bali bombings:

Though Sidia and the other artists are mere humans, in the time that they played the wayang they stepped into a place of power where the disorder can be mediated by the active power of performance. There humans mediate the divine and nature as in the tri hita karana [three elements of harmony: environment, man and divinity]. There they can reveal the dangers of the sad ripu [the six internal enemies: lust, greed, anger, confusion, drunkenness, and jealousy] and help promote the proper relation of the dasanama kerta [the ten elements: earth, water, fire, air, fish, animals, birds, plants, humans, and gods]. Even in the newest permutation—wayang kontemporer—we see one of the old impulses of Balinese puppet performance: art actively reorders the universe and humans become like gods when they enter the realm of art (I Nyoman Sedana 2005:85, emphasis added)

I haven't found any instance of people in Java speaking about wayang kontemporer performances in a similar way. This confluence of aesthetic innovation and religious efficacy is perhaps specific to Bali. In the case of Malaysia, wayang kulit siam has notably been subject to bans, but even before that it never enjoyed the same visibility or importance as Javanese wayang within its own sociocultural context or in international scholarship. As Ghulam-Sarwar Yousof notes:

It is clear that the shadow play in Malaysia was never an important or even a popular medium that is comparable to that in Java or Bali. Nor was there any kind of official support for it, including from the courts (Yousof 1997: 9).

Although wayang kulit in Kelantan and Bali offer interesting contrasts to wayang kontemporer in Java, a comparison with contemporary forms in these places would make this an entirely different project, and would require a linguistic expertise beyond my current abilities. Therefore, I have chosen to concentrate on specific wayang practices in Java, which I describe as hybrid performances, located in between wayang and something else (See Aesthetics).

These performances are combinations of “tradition” and “other media,” as these ideas are imagined today. Tradition is certainly a constructed term, but nevertheless a useful category for analysis. The way tradition is imagined, talked about and performed is subject to change and that which is considered as traditional today was not necessarily so in the recent past. The work of Natosabdho (1925-1985), for example, is generally accepted today as a model of tradition. However, in his times, his usage of lakon karangan [composed stories] was controversial and he was considered a “destroyer of tradition” (Petersen 2001: 106). After Indonesian independence certain shows have been talked about as instances of wayang modern, wayang kreasi and, more recently, wayang kontemporer. The objective of this dissertation, however, is not to trace the transformation of the notion of tradition nor of attitudes to that tradition within Javanese performances. It takes as its starting point tradition as a contemporary discourse. It accepts the fact that tradition is often an artificial, dynamic and contested term. However, as far as this research is concerned, tradition is what it is said to be today. This will not erase inherent disagreements in this notion; the concept of tradition also means tradition as it is disagreed about today. In any case, these hybrid performances represent, mock and repurpose tradition as it is imagined in the current world of wayang practice. I subscribe to the approach outlined by Jan Mrázek in the following words:

When I talk about ‘new' trends, I am not suggesting that one could not find precedents for these trends in a more distant past (I point out historical precedents in some but not all cases). I merely imply that today they are (still) felt as new (Mrázek 2005: 362).

In my interpretation, these hybrid performances are creative responses to two sets of questions. The first one is formal – that is, it is concerned with the form of wayang. What can wayang be? How can it sound, feel, and look like? How long should it last, where and to whom shall it be presented? Which language should be used to perform it? The second set of questions is philosophical. At its core, all wayang is concerned with how to live. These kontemporer shows ask: How should one lead life in these crazy times? How should one relate to others, to tradition, to outsiders, to the state? To what extent are the old Javanese ethics still relevant and to what extent are they in need of revision or dismissal?

These questions are important because they strike a chord with contemporary audiences. They matter, specifically, to young people living in post-Suharto, digitally connected and cosmopolitan cities in Java. Whether they are specifically concerned with wayang or not, all the young people I have met in Indonesia are dealing with some version of these questions, day in and day out. They are constantly making aesthetic and ethical decisions, choosing to what extent they should follow what their parents and teachers tell them and to what extent they should find hybrid modes of thought and expression that adapt influences from other places. They are experiencing in the flesh the ‘post-traditional' anxieties that come with the “reflexive modernity” described by Anthony Giddens:

The reflexivity of modernity extends into the core of the self. Put in another way, in the context of a post-traditional order, the self becomes a reflexive project [...] In the settings of modernity, by contrast, the altered self has to be explored and constructed as part of a reflexive process of connecting personal and social change (Giddens 1993: 304).

How to dress? How to represent yourself to your friends and family, online and offline? How to deal with emotional relations? How to build a future? How to act? What language to use? How to speak? What to say? Basic tenets are up for debate in a way that is perhaps unprecedented in Indonesia. It can be rightly said that some citizens of the country were engaged in intensive soul-searching after Independence, but the options open to ordinary people were severely curtailed shortly after, by the policies of the New Order. It is only recently that a progressive democratic restructuring of institutions, a growing middle-class and the digital revolution have enabled millions of young people to ask themselves these questions on a daily basis.

Wayang kontemporer offers creative responses to these issues within the most contested, venerated (and hated) art practice of Java. The present dissertation addresses how people answer these questions through wayang kontemporer. It is about the words used, the stories told, the music played and the puppets made, as much as it is about the messages being conveyed.

So far, I have emphasized a distinction between the form and content of wayang kontemporer. This deliberate strategy is a result of specific ways in which people have talked to me about wayang. I once asked my teacher Pak Parjaya, who is a traditional dalang, about his thoughts on the work of the kontemporer practitioners.

There is no problem if you want to do kontemporer things, as long as they contain something! [Nggak apa-apa kalau mau kontemporer, selama ada isinya!]

I was sitting in his office in Ngaglik, a village north of Yogyakarta where an ambitious, world-bank funded arts education initiative was set up in the 1990s. We were eating tiny kue (biscuits) that were wrapped in banana leaves. He said:

The kue is not the same as the leaves. You could present the kue in other forms, wrap it with other materials. It is the same with wayang. The important thing is not the wrapping, but the philosophical values it conveys. If some people are creative and can create new wrappings, that is very good, because it will get young people interested in the tradition. It will allow people to continue eating kue.

Other people have spoken to me about kontemporer shows in comparable ways. In my experience, people tend to emphasize this form/content distinction when talking about their work and the work of others and, therefore, I will use this way of talking about wayang in my writing as well.

Most western performance scholarship is weary of form/content distinctions. For historical reasons that I will examine, some writers have become suspicious of these distinctions. In Indonesia, however, for another set of historical reasons, this distinction is a relatively new and very current way of talking about the creation and experience of art.

For a long time, making distinctions of form and content was part of the western academic tradition of philosophizing about art. As Arthur C. Danto notes:

It had always been taken for granted that one could distinguish works of art from other things by mere inspection, or by the sorts of straightforward criteria by which one distinguishes, say, eagles from palm trees. It was as though artworks constituted a natural kind but not a philosophically natural kind, and that one mastered the concept of art by learning to pick out the examples (Danto 1992: 7).

This distinction was brought to a crisis by modernist artworks and more powerfully, according to Danto, by the works of Andy Warhol, such as the Brillo Box: “the Brillo Box really does look so like boxes of Brillo that the differences surely cannot constitute the difference between art and reality” (Danto 1992: 7). Talking about a distinction of form and content at this point would be useless and misleading. In the Brillo Box, as in many conceptual pieces, there is clearly no ‘content' that can be separated from the form of the artworks. Of course, this is just the culmination of a process that started almost a century earlier. As Lehmann writes, “ever since Cézanne in painting and modern French poetry in literature the autonomization of the signifier has been observable, its play becomes the predominant aspect of aesthetic practice (Lehmann 2001: 64).” The autonomization of the signifier is just another way of saying that the form does not ‘have' content: it is what it is. The form and/or signifier do not stand for things other than themselves. Lehman links this to developments in theatre as well, in what he terms postdramatic theatre:

In the face of our everyday bombardment with signs, postdramatic theatre works with a strategy of refusal. It practices an economy in its use of signs that can be seen as asceticism; it emphasizes a formalism that reduces the plethora of signs through repetition and duration (Lehmann 2001: 89-90).

He would later suggest that this formalist, postdramatic theatre, “can be seen as an attempt to conceptualize art in the sense that it offers not a representation but an intentionally unmediated experience of the real (time, space, body): Concept Theatre” (Lehmann 2001: 134). This unmediated experience is also the goal of performance art. Content/form distinctions would certainly be useless to describe Marina Abramovic inflicting wounds on her skin. The vocabularies of performance art and of postdramatic theatre have certainly affected the ways in which theatre is talked about in contemporary scholarship and many performances will be ill-served by a terminology that would simplify their complexity to the binary of a form/content analysis.

However, this terminology and dyad would not be simplistic in Java. Modern art and modern performance operate in a very different way in Indonesia. Wayang kulit was a preeminently ritual form until the early 20th century. According to Clara van Groenendal, wayang emerged as a contemporary art form in the 1920s when it was taught in schools (Groenendael 1972). Emphasis was placed on learning the technique, which then became freed from its ritual significance. This paved the way for the innovations that led to the wayang kontemporer of the 21st century. Catherine Diamond, in her comparative study of contemporary Southeast Asian theatre, offers a similar explanation. She identifies “the establishment of state institutions” as one of the factors that have preserved the traditional arts but “also altered their function in society” (Diamond 2012: 4). However, she also considers “colonialism's imposition of foreign aesthetic criteria” as a cause of the same condition. In a point that seems to echo Groenendael, she describes that which happens in “western influenced” (Diamond 2012: 4) institutions:

While students learn technique, they have lost the meaning of the dance movements, the symbolism in song lyrics, the connotations of a melody, or the religious/philosophical significance of a narrative (Diamond 2010: 4).

I agree with her analysis but disagree with her nostalgia. With the advent of these teaching methods, meanings have not only been lost. The possibility for new meanings has also been gained. Form and content are now offered as separate realms for artistic exploration, questioning and innovation. In Java, after the preeminence of ritual, a local understanding of modernism and postmodernism allows artists to explore new ways of representing old ideas, and using old forms as vehicles for new ideas. This dissertation explores how these new meaning and ideas are constructed. It examines the ways contemporary dalang have modified wayang to talk about environmental concerns, spirituality, politics, the functions of art, and the role of women and young people in a changing society.

I do not wish to suggest that form and content are always dissociated. But I believe that separating them for the purpose of this analysis is a productive way to discuss the performances. Not all radical aesthetic explorations are coupled with radical thematic explorations. By maintaining a double focus, it is possible to recognize continuities and differences in both the formal and the thematic explorations of the new work developed by the dalang.

My proposed approach could still be accused of being a simplification of what is, in reality, a more complicated thing. I would answer to this argument that certain simplifications are useful and more desirable than their opposites: excessive complications that lead nowhere. I would like to illustrate this point by referring to two short stories by the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges.

Funes, el memorioso [Funes the Memorious] is a man who had the capacity to remember everything. But he was not capable of making abstractions. “To think,” concludes the narrator, “is to forget” (Borges 1997: 76). This dissertation is an attempt to think about wayang; that is, to forget some aspects of its complexity in order to highlight its complexity. For the sake of drawing attention to important things, this dissertation will necessarily overlook other important things. The metaphors used by Slamet and Parjaya will provide the basic interpretive framework for this endeavor, which I will now outline by describing how the dissertation is organized into chapters.

Chapter 1: Methods and Context. This dissertation has three objectives: to compare the features of wayang kontemporer performances in order to analyze their heterogeneous creativity, to interpret what they say about life in contemporary Java, and to reflexively develop a digital platform in order to convey my analysis of these performances. In this chapter, I set the theoretical background to sustain these objectives by presenting an overview of previous scholarship on wayang, highlighting my positionality as a digital archivist, and describing a methodological approach informed by performance studies and digital humanities.

In the following chapters, I propose a set of concepts that will guide my analysis: variables of adaptation and ethical explorations. The variables of adaptation are the formal building blocks of a kontemporer performance: puppets, music, space, story and language. Based on my conversations with dalang, I suggest that these are the building blocks with which dalang work and think when developing new works based on the tradition. The ethical explorations outlined in the next chapter constitute the themes addressed by these performances. Based on my conversations with the artists, I suggest that the ethical interpretation of the stories is very important to the dalang, who think about this carefully and constantly when devising their work.

In Chapter 2: Variables of Adaptation I describe the variables of adaptation, the aesthetic adventures that start in wayang but end in hybrid performances. The main building blocks of kontemporer performances (stories, music, language, space and puppets) can be used in three ways: reproducing conventions, reinterpreting them or substituting them for conventions from outside of wayang. In each of the sections in this chapter, I follow the trails of each of these explorations. I begin each section with anecdotes that illustrate the importance of each of these building blocks and then move on to offer detailed descriptions of all the variations in the kontemporer performances considered in this dissertation. Then, I venture into a philosophical interpretation of the implications of such classification. For example, when looking at the substitution of communal, improvised gamelan music for pre-recorded hip-hop soundtracks with star performers, I suggest that this could be interpreted as a sign of a historical change in how creativity is conceived in Java. Although this analysis is predicated on similarities, I attempt to remain attentive to differences among individual performances. Therefore, I describe the aspects of each performance in detail, trying to account for nuanced distinctions within a given category. The texts can also be read as a result of the interaction with the diagrams of each performance.

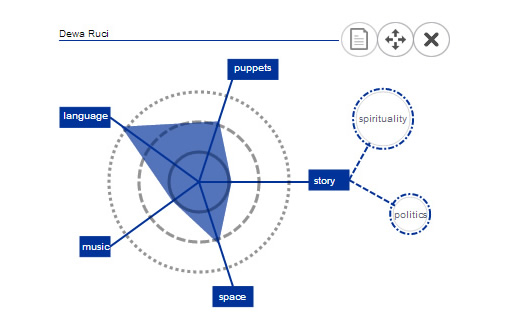

In these radar diagrams, the five variables are represented by arrows. Three circles of progressive diameter represent the possible values: conventional (marked by a solid line), non-conventional (dashed line) and mixed (dotted line). A skewed pentagon indicates the value of each variable within a given performance. The degree of conventionality is defined by the five vertices (the intersection of the line and the circle). In other words, the farther away a vertex is from the center, the least conventional the variable it represents. The following radar diagram, for example, represents Dewa Ruci, which uses a non-conventional language, mixed puppets, a conventional story, and mixed space and conventional music (Figure 1.1). When placing the mouse over any of the labels, small pop-up windows appear with further explanations on why a particular value was assigned to a given variable.

These radar charts were chosen since they fit the classificatory model developed in this dissertation (a multivariate model). However, it is clear that the diagrams are not neutral. They have rhetoric strength and enact particular understandings of the play. In this case, they emphasize that which is far from the tradition (as the shapes become bigger the more a performance departs from conventions).

I will describe the spheres that spread from the "story" label later in this introduction. When users click on any of the categories, the corresponding dissertation chapter will appear in the text window (which is currently occupied by this introduction). The usage of this diagrams has advantages and disadvantages. The most obvious shortcoming is that they flatten all the performances, subsuming internal differences and suggesting they are all the same kind of entities. I try to counter this shortcoming by offering a more nuanced description in the texts. The main advantage of the diagrams is that they allow for a visual comparison of the elements across performances. They also work as reading aides. Users not familiar with all 24 performances analyzed in this dissertation can summon up the diagrams in order to facilitate reading by easily conjuring up the main characteristics of each performance.

To some readers, the diagrams might suggest an attempt at scientific objectivity. However, my objective is not to offer truth claims about these performances. Rather, I intend to render my personal experiences of these performances in a way which is visual, interactive and comparative. The variables for the variables of adaptation and ethical themes were not created a priori, but as a result of the multiple viewing of the twenty-four performances in the collection analyzed in this dissertation. Furthermore, the texts for each category are animated by an essayistic imagination (see Approach: An Essayistic Ontology) rather than by objective explanations. Therefore, readers might certainly identify discrepancies with their own views. These texts are meant to be playful, partial and interpretive explorations of ideas, informed by conversations, experiences and readings.

Chapter 3: Ethical explorations is concerned with the biscuits. It is conceived as a series of guided tours of the maze of the performances taken together. It cuts across chapters, following thematic associations through the different performances. This chapter is mainly concerned with the ethical explorations suggested by these shows: that is, what wayang says about life. The emphasis on ethics is underpinned by an approach to the exegesis of the stories which is common in Java. In my experience, people often discuss performances in terms of their ethical relevance. Discussions tend to focus on what wayang performances say about ethical behavior under particular circumstances. This is also important to the dalang who create these shows.

The ethical discussions are the main hermeneutic strategy I was offered when I discussed the stories with the dalang. This is represented visually in the diagrams by the small circles branching out from the “Story” variable. While Chapter Two deals with the origin of the stories (whether they come from traditional sources or not, and what this says about wayang), this chapter focuses solely on the ethical implications of the stories, regardless of their origin. These discussions are organized around seven themes: familial ties, women, youth, spirituality, environmental concerns, politics and art. The texts distinguish between two ways in which the themes can be addressed in a performance: they can be the central concern of the narrative, or they can be tangentially addressed. Although I distinguish between these two modes of thematic engagement, I suggest that tangential references to a theme are important in wayang kulit. Dalang always weave references to the contemporary world into the fabric of the performance through asides, off-the-cuff remarks and interactions with the singers and musicians. The meaning a wayang takes in the minds of spectators is often more connected to these remarks than to the theme explored through a particular story.

In the diagrams, as mentioned above, the themes are represented by circles, linked to the "story" variable. The size of the circle indicates weather the particular theme was presented through plot development (big circle) or through tangential references (small circle). To continue a previous example, we can look again at the full diagram for Dewa Ruci (Figure 1.2). Here two themes are identified: spirituality (which is discussed through plot development) and politics (explored through a tangential reference in the comic interlude).

By clicking on the circles, users can read the full texts that trace the themes across multiple performances. The subsections can be read on their own, or together as a whole chapter. In the same way as the texts that discuss the aesthetic variables of adaptation, the texts are selective readings of the performances and the readers will certainly identify omissions or excessive emphasis on certain ideas.

In my view, the texts and the diagrams complement each other, balancing out different objectives and possibilities, a point I expand in Approach: An Essayistic Ontology. When engaging with the ideas and assessing their limitations, I would like the reader to think of these texts as guide books. Like many guide books, they are selective and limited. But they can also be thought of as productive starting points for multiple journeys. In other words, they are suggestions, and not absolute dictums. I hope that users will explore this digital dissertation with joyful flânerie. As Bruno Latour writes:

The advantage of a travel book approach over a ‘discourse on method' is that it cannot be confused with the territory on which it simply overlays. A guide can be put to use as well as forgotten, placed in a backpack, stained with grease and coffee, scribbled all over, its pages torn apart to light a fire under a barbecue. In brief, it offers suggestion rather than imposing itself on the reader. (Latour 2007: 17)

I hope this invitation for flânerie will be facilitated by the digital platform I built for this dissertation, so that users can navigate from the performance diagrams to the texts and videos that constitute their analyses. Selamat jalan!

CLOSE [X]